More than a day at the border needed to make sense of it

A year after visiting the Arizona-US border, some perspective emerges

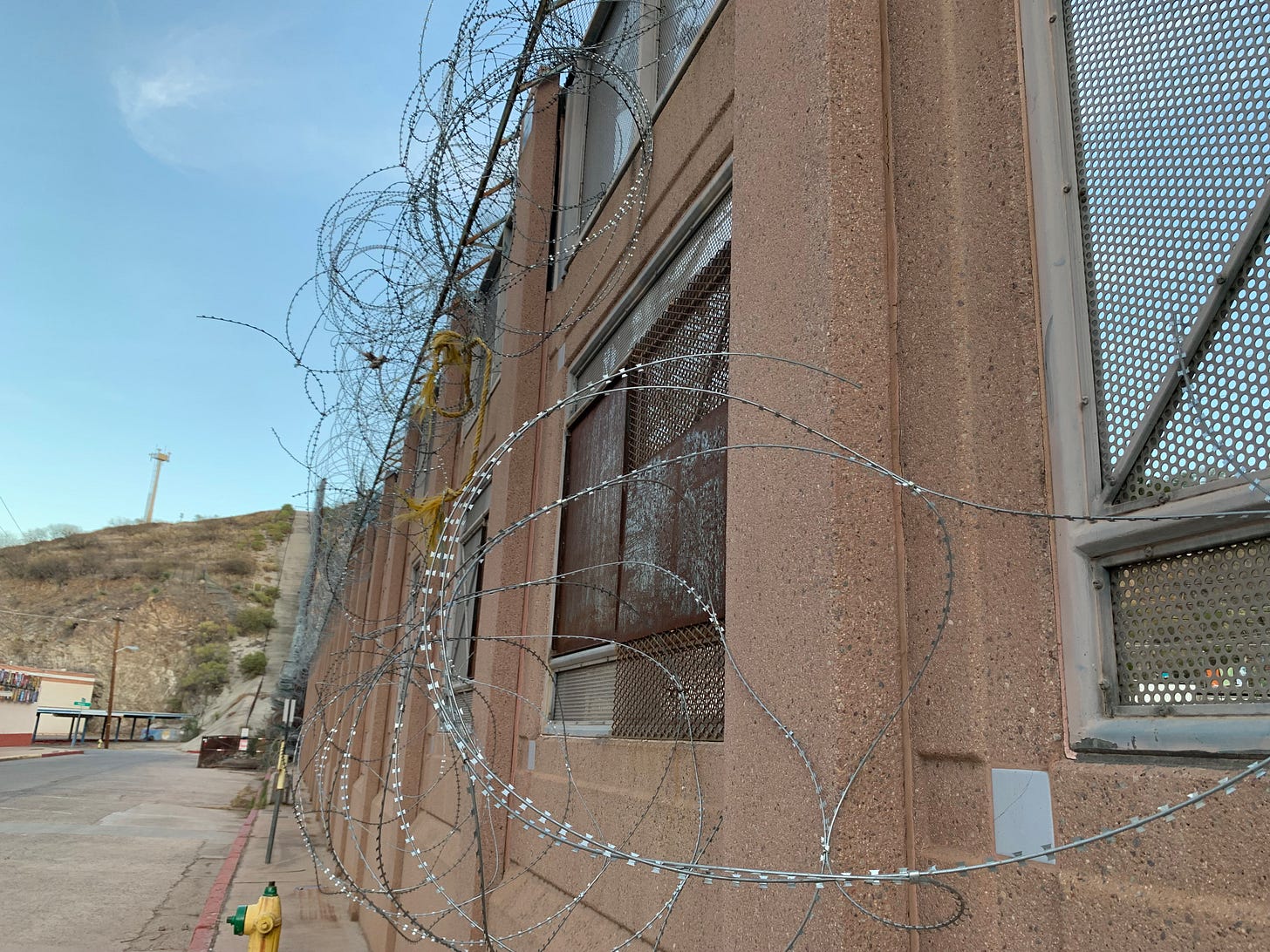

Razored, barbed wire fence is among the barriers at the U.S.-Mexico border in Nogales, Arizona. (Photo by Lyle Muller)

A year ago, three other journalists and I were bouncing across a god-forsaken desert trail between Sasabe and Nogales in southern Arizona. The trail was rough, though not as rough as what immigrants crossing the U.S. border illegally encounter.

It was Jan. 15, 2024. My fellow Iowans who cared enough about politics to make their voices known were prepping to attend that night’s presidential precinct caucuses. This was the first precinct caucus night I did not spend in or attached to a newsroom since 1972.

The four of us wanted to see and understand better what we were told was chaos at the border. It was a mellow day. Not much chaos. That did not mean it had not existed. It just was not on this particular day, plus, we were out in the afternoon. The main traffic in this spot moves at night.

I wrote a column that was published in the February 6, 2024, Cedar Rapids Gazette. I have posted it here with some notations because the anniversary of that promped me to take another look at the column. Updated commentary is in italics.

The “crossroads” for the main characters near the U.S.-Mexican border in southern Arizona. (Photo by Lyle Muller)

Watch for the drones, Matthew Casey, a reporter for KJZZ public radio in Phoenix, Arizona, said. That’s the new way the U.S. Border Control officers look for drug smugglers and human traffickers along the border with Mexico in southern Arizona.

He was speaking in an area known as a crossroads for all of the main characters in this part of the country. They include refugees from Mexico and Central America, the Border Patrol, the smugglers — of both people and drugs, explained Casey, who has covered immigration and the border for more than a dozen years.

He was speaking to two other journalists and me. Going to the U.S.-Mexico border was a heck of a way to spend Jan. 15, 2024, the day when Republicans and Democrats in Iowa were caucusing in a deep freeze. But a lot of talk, including about the border, goes on when dealing with politics at events like the caucuses. Having the good fortune of being in Arizona instead of precinct caucus, three Arizona journalists and a lone Iowan decided to satisfy a curiosity: How bad is it?

This area south of Tucson touches a border we are told is awash with invading bad characters. Iowa’s political leaders have made points about this happening in Texas, who governor is claiming state’s rights in the face of a Supreme Court ruling, with support from 26 governors who including Iowa’s.

But, Arizona? We don’t hear a lot up north. There, on the border, sits Sasabe, population nine people, although more live in nearby ranches. The local store owner is asked about claims of border chaos. “Do you see any chaos?” she asks. Not really. A guy came in to buy two tamales for $3.75 each. A few more cars stopped for lunch and gas.

The store owner said she didn’t want to give her name because a news media outlet published a photo of her store when someone was murdered 50 miles south in Mexico.

Well, that’s one story from the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge desert where Sasabe is situated. There are others that the store owner skipped over, including gang warfare just the other side of the border wall in Sasabe, Sonora, Mexico, in November and December and people fleeing from there to Sasabe, Arizona. Or, the white vigilante who kept going across the border and into Mexico east of Sasabe while chasing an unarmed man back into that country in April 2023.

The Texas Observer and Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting did a collaborative, in-depth piece on vigilantes in May 2024. The vigilantes wear camouflage and battle gear and shoot video of themselves on patrol and with law enforcement officers to seek donations, the reporting showed. They also raise the threat of violence and raise questions about how much they are doing that is legal, the report says.

Talking with Border Patrol in southern Arizona. (Photo by Matthew Casey)

There were plenty of Border Patrol on this day. A group of agents with four cars and an all-terrain vehicle taking off flak jackets hinted to having a good night. We stopped and asked how good but they wouldn’t talk about it.

A drive east from Sasabe along a rough, dirt trail to the village of Arivaca was quiet. People were friendly enough in the Arivaca cantina while they watched an NFL playoff game on television. Farther east, in Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, the cultures, people and businesses appeared to integrate peacefully. North of Nogales, a town that flies the U.S. and Mexican flags side-by-side on light poles, miles of refrigerated warehouses line Interstate 19, holding fruits and vegetables harvested in Mexico and tabbed for distribution across the United States.

Yet, there are signs that not all is well in this part of the world. Sasabe, Sonora, is virtually vacant, reports from there state. People have been murdered there in a fight between rival drug cartels. On the north side of the wall, Sasabe, Arizona, is mostly a handful burned out buildings, except for the general store, post office and a bar that’s open Saturdays only. Armed men were arrested at Sasabe’s border in December.

Things have not gotten better since the end of 2023. Two people were reportedly shot at the border in December 2024. The gang violence, fueled by drug lords wanting to claim territory, continues.

During the past year, I keep thinking about the desert area. Our little group stopped at a few spots. In one area, we stopped to clear brush from hitting the car. In another, we stopped to avoid dropping into a three-foot-deep, two-foot-wide rut. At another, I spotted a cross beneath some trees and wrote about it in the 2024 column.

(Photo By Lyle Muller)

Along that desert path between Sasabe and Arivaca, a four-foot-tall hand-made cross sticks up from the rocks underneath a tree, its purpose untold.

Here, the newspaper cut explanatory information I had written because of space concerns, but a Tucson.com news story cited in the draft I submitted revealed that a Tucson artist named Álvaro Enciso fashions these crosses. He and a group of volunteers go into the desert and place the crosses where immigrants have died while trying to get into the United States. Enciso’s project is called “Donde Mueren Los Sueños,” which means “Where Dreams Die.”

Our group stopped for lunch in Arivaca, a tiny village near the border, between Sasabe and Nogales.

An Arivaca rancher says he heard a gunfight from the Mexican side of the border in December.

The desert looks foreboding for any kind of surreptitious trip to freedom in the United States.

Swooping in for a day – and that clearly was what this trip was – tells you little about the complexity of dealing with the U.S.-Mexico border. Arizona’s border is different than California’s, New Mexico’s or Texas – three states I did not visit. The biggest thing I learned on a one-day attempt to view some facts is that you only get the tiniest glimpse of how this all plays out.

Understanding the border requires a grasp of U.S. immigration policies, Mexico’s inability to curb drug cartel crime, gang violence in Central American countries from where many undocumented immigrants come, but also the reason so many people have wanted to be in the United States for more than two centuries – to make a better life for themselves.

You might want to consider that when you see politicians going on border trips or talking about experiences there. “Iowa stands with Texas,” Gov. Kim Reynolds stated Jan. 25 on the X social media platform. She and U.S. Rep. Ashley Hinson, R-Iowa, are among the many Republican leaders supporting Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s declaration that Texas has a state constitutional right to disobey a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on removing razor wire from the border.

The Iowa Legislature is considering bills that require Iowans to show proof that they are in the United States legally in order to receive in-state tuition at a state university or to get help from public assistance programs.

The proof of citizenship bill for in-state tuition did not make it to the floor for a vote in the 2024 legislative session. The bill for public assistance passed the House but was not dealt with on the Senate floor. Both issues remain alive for the 2025 legislative session.

Iowa’s political leaders should visit Arizona’s border if they want a full picture of what is happening. California and New Mexico, too. And, focus on real immigration issues that put the border in play as a political opportunity.

We think we know what’s happening along that border but we really don’t, especially from a day trip that turned out to be as superficial as presuming we know in an Iowa precinct caucus or the Statehouse.

A recent Gallop Poll reported that 68% of U.S. adults in the survey of 1,003 Americans from Dec. 2-18, 2024, think Donald Trump can fix problems going on at the U.S.-Mexican border. The margin of error was plus or minus 4 percentage points.

How long he stays in the good graces of not only Americans but grassroots Republicans remains to be seen. The incoming president visited the border region during his 2024 campaign. Now comes the real work.

Left to right, journalists Matthew Casey, Lyle Muller, Mark Casey, and (with cap) Terry Wimmer at the U.S.-Mexico border in Sasabe, Arizona, on Jan. 15, 2024. (Photo by Matthew Casey)

Lyle Muller is a board member of the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting and Iowa High School Press Association, a trustee of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council, former executive director/editor of the Iowa Center for Public Journalism that became part of the Midwest Center, former editor of The Gazette (Cedar Rapids), and a recipient of the Iowa Newspaper Association’s Distinguished Service Award. In retirement, he is the professional adviser for Grinnell College’s Scarlet & Black newspaper.